The following post offers a little idle speculation to help pass the time on the question of whether there was any Hunnic influence on fifth-century Britain and whether the 'Anglo-Saxons' were, in part, descended from Huns. Needless to say, at first glance the idea seems ludicrous! A

fter all, in Book I, chapter 15, of his Historia Ecclesiastica of 731, Bede famously wrote of the mid-fifth century that:At that time the race of the Angles or Saxons, invited by Vortigern, came to Britain... They came from three very powerful Germanic tribes, the Saxons, Angles and Jutes.(1)

There are, of course, no Huns mentioned here. Instead, the Germanic immigrants to post-Roman Britain are identified as having come from three pre-existing tribes who seem to have lived in northern Germany and Denmark, with Bede going on to identify the people of Kent, the Isle of Wight and parts of modern Hampshire in his day as Jutes; those of the kingdoms of Essex, Sussex and Wessex as Saxons; and those of East Anglia, Middle Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria as Angles. However, whilst Bede's account has undoubtedly proven influential and may well, in part, have a significant basis in reality, caution is also needed. Indeed, with specific regards to the potential continental origins of the post-Roman immigrants to Britain, it is likely that things were somewhat more complicated in the immediate post-Roman era than the above passage might indicate, with Bede's insular Anglian and Saxon identities now often thought to have resulted, to some degree, from a blending and reconstruction of immigrant material cultures and identities in the early Anglo-Saxon period, most especially the sixth century.(

2)

One example of this potential complexity can be had from the archaeology of 'Anglian' Britain. Whilst John Hines has rightly observed that 'the core of the Germanic culture that appears in East Anglia', forming the basis of the Anglo-Saxon material culture there, points towards 'the Anglian homelands... primarily in what is now Schleswig-Holstein', he also argues that the archaeology of this region exhibits additional strong cultural links with western Scandinavia right up to Sogn og Fjordan, Norway, which are most credibly explained via a degree of immigration from that area too in the post-Roman period.(

3) Equally, Vera Evison once made the case for a significant Frankish element in the archaeology of post-Roman Britain south of the Thames, and whilst this is no longer accepted in its entirety, there does seem to be sufficient material to suggest at least some Frankish immigration to this region in the 'early Anglo-Saxon' period. Less certainly, other archaeological material has also been cited as possible evidence for the presence of small numbers of Thuringians and even potentially Visigoths in post-Roman southern Britain.(

4)

![]() |

| A probable late fifth- or early sixth-century buckle tongue, which has its best parallels in finds from Norway and Estonia; found Thimbleby, Lincolnshire (image: PAS) |

Other, non-archaeological evidence similarly hints at the presence of ethnic groups in early Anglo-Saxon England that were not mentioned by Bede in

HE I.15. For example, not only has it been suggested that the East Anglian royal

Wuffingas were potentially either of Swedish/Geatish origin or claimed to be so, but Barbara Yorke has also observed that the Kentish ruling dynasty, the

Oiscingas, appears to have claimed Gothic descent for themselves. So, the name of their dynastic progenitor, Oisc, would seem to be cognate with that of the Ostrogothic demigods, the Ansis; the father of King Æthelberht of Kent, Irminric/Eormenric, bore the name of one of the most renowned early Gothic heroes; and Asser in the ninth-century seems to be aware that the Jutes claimed a Gothic identity when identifying King Alfred's maternal grandfather, who was apparently of the Jutish royal line of the Isle of Wight, as 'a Goth by race'.(

5) Likewise, the sixth-century Byzantine historian Procopius reported that Britain was inhabited by Britons, Angles and Frisians—rather than Saxons or Jutes—when he wrote in the 550s, a statement that continues to be the source of some controversy.(

6)

Finally, there are a variety of early English place-names that are thought to make reference to the presence of continental tribal-groups and identities in pre-Viking Britain other than those Bede lists. So, the Swaffhams in Norfolk and Cambridgeshire appear to be early names that mean 'the estate of the

Suebi or Swabians' (an ethnonym that is incidentally also found in

Suebdæg, a personal name that occurs in the royal genealogy of the Anglian kings of Deira). Similarly, Elm in Cambridgeshire might potentially reflect a settlement of the continental

Elvecones and Tealby in Lincolnshire is now generally agreed to have originally indicated a settlement of a group of

Taifali, a continental tribal-grouping that has been variously identified as East Germanic—linked to the Goths—or even Asiatic in origin. Moreover, yet other place-names have been thought to be indicative of the presence of Burgundians, Danes and Thuringians in England during the early Anglo-Saxon period.(

7)

In sum, whilst Bede's account in

HE I.15 of Angles and Saxons in eastern Britain may well have a significant basis in reality—as Hines, Williamson and others suggest—the situation in the fifth and earlier sixth centuries was nonetheless clearly rather more complex than Bede's account implies. 'Migration Period' Britain also appears to have included individuals and groups drawn from continental tribes and confederations that Bede omits to mention in that chapter, including potentially some of East Germanic origin, and the recorded insular Anglian and Saxon identities are thought, in part, to have resulted from a post-migration blending and reconstruction of cultures and identities. In such a light, it seems clear that the absence of Huns from the famous account of the post-Roman continental immigrants in

Historia Ecclesiastica I.15 cannot be actively used to

disprove the notion that there were Huns present in fifth-century Britain. However, this is by no means the same as saying that they were definitely here then! So the question becomes, is there any actual

positive evidence which might support the idea that there was a degree of Hunnic presence in and/or influence on post-Roman eastern Britain?

![]() |

| A late fifth- or early sixth-century Visigothic iron bow-brooch, found Springhead, Kent (image: Wessex Archaeology, used under their CC BY-NC 3.0 license). |

Perhaps surprisingly, the most important potential piece of evidence in favour of a Hunnic presence in early Anglo-Saxon England comes, once again, from Bede's

Historia Ecclesiastica, in this case Book V, chapter 9. In this chapter, Bede returns to the question of the tribal origins of the Anglo-Saxons during a discussion of the missionary activity of Egbert, offering what reads like a rather more nuanced and complex version of his earlier statements on the topic:

He knew that there were very many peoples in Germany from whom the Angles and the Saxons, who now live in Britain, derive their origin... Now these people are the Frisians, Rugians, Danes, Huns, Old Saxons, and Boruhtware (Bructeri); there are also many other nations in the same land who are still practising heathen rites to whom the soldier of Christ proposed to go... (8)

Needless to say, this is a passage of considerable interest in the present context! It is, however, also a section of Bede's text that has caused some difficulties and controversy in the past, sometimes being ignored entirely, mentioned only in passing, or treated as merely a list of peoples Egbert intended to visit and preach to in eighth-century Germany, rather than a list of peoples that the Angles and Saxons had their origins in (with the mention of 'Huns' being thus interpreted as an allusion to the eighth-century Avars).(

9) The first two responses are, of course, not really solutions at all, whilst the third is open to serious question. Thus James Campbell has argued forcibly that Bede was

not saying that the list in

HE V.9 was made up of peoples who lived in Germany that Egbert wished to convert; rather, he states that 'the sense of the Latin is that these were the peoples from whom the Anglo-Saxons living in Britain were derived.' It may be surprising or even inconvenient, 'but it is what he [Bede] says; and he does not generally write carelessly.' In other words, Campbell considers that Bede—a notoriously careful writer and historian—clearly believed that the Anglo-Saxons of his day derived somehow from the peoples that he listed, and that these peoples included the Huns.(

10)

If the text of

HE V.9 does indeed mean what it says, then it would provide a significant degree of confirmation for the position outlined above—that whilst Bede's division of post-Roman eastern Britain into 'Anglian' and 'Saxon' areas may well have had a significant basis in reality, so too was the situation in the fifth and earlier sixth centuries probably rather more complex than can sometimes be assumed. Certainly, Bede's second passage has often been understood and used in just this way by those studying the post-Roman period, and it would moreover even seem to support some of the specific suggestions made above as to other continental tribal groups potentially present in post-Roman Britain, with Frisians and Danes both mentioned previously and the

Boruhtware (Bructeri) of Bede's passage being usually considered a Frankish group.(

11) Furthermore, it has also been argued that a genuine early tradition or even source could well lie behind what Bede says in

HE V.9, on the basis that 'these names belong to a fifth rather than eighth century context', with not only Huns and Bructeri being referenced—both names from the 'Migration Period'—but also the

Rugini/Rugii, a tribal group that seems to have only really came close to Britain in the mid-fifth century, when they are said to have taken part in Attila's Hunnic invasion of Gaul in 451 alongside the Bructeri.(

12)

We would therefore seem to have at least some potential positive evidence in favour of a Hunnic presence in post-Roman eastern Britain, on the basis of the above understanding of

Historia Ecclesiastica V.9. However, even if a genuine tradition or even an early source does lie behind Bede's statement, we still need to ask what exactly this might imply with regard to fifth-century individuals and groups in eastern Britain. Ian Wood has, for example, considered that the claim that the Anglo-Saxons in part 'derive their origin' from Huns may, in reality, have resulted from there having been an Alan contingent amongst the post-Roman migrants to Britain (they were certainly present in northern Gaul in the first half of the fifth century), with the ethnic-term 'Hun' being used broadly for any 'Asiatic' people present here then, rather than being used specifically for Huns alone.(

13) As such, the question necessarily becomes, is there any other evidence which might support the idea that Huns were specifically present in and/or had a degree of influence upon post-Roman eastern Britain?

![]() |

| The Roman Empire and the Hunnic Empire of Attila in c. 450; click image for a larger version (image: W. Shepard, Historical Atlas (New York, 1911), p. 48, Public Domain). |

The second piece of evidence that might potentially indicate a degree of Hunnic involvement with fifth-century Britain actually derives from a mid-fifth-century and very well-placed source. The text in question was written by Priscus of Panium, an Eastern Roman diplomat who visited the court of Attila the Hun as part of an official delegation in AD 448/9. The account that he subsequently wrote only survives through fragments and excerpts but it nonetheless offers an enormously valuable, first-hand description of Attila's court and the Roman diplomatic contacts with this. In the course of relating his experiences, Priscus tells of how his party met up with an embassy from the Western Roman Empire and cites what one of the western ambassadors, Romulus, had to say on the topic of Attila's character:

When we expressed amazement at the unreasonableness of the barbarian, Romulus, an ambassador of long experience, replied that his very great good fortune and the power which it had given him had made him so arrogant that he would not entertain just proposals unless he thought that they were to his advantage. No previous ruler of Scythia or of any other land had ever achieved so much in so short a time. He ruled the islands of the Ocean and, in addition to the whole of Scythia, forced the Romans to pay tribute. He was aiming at more than his present achievements and, in order to increase his empire further, he now wanted to attack the Persians.(14)

The Western Roman ambassador's comments on the extent of Attila's empire in 449 are, of course, of considerable interest in the present context, in particular his statement that Attila 'ruled the islands of the Ocean'. The exact import of this statement is, of course, crucial. Although E. A. Thompson wrote in 1948 that 'historians now agree that the islands ruled by Attila were those of the Baltic Sea' (a statement that has been borrowed and repeated by some later commentators), this is not actually true. In the early twentieth century, for example, both Theodor Mommsen and J. B. Bury regarded an identification of these island dominions of Attila with the British Isles to be probable, and such an identification has been more recently supported by C. E. Stevens, James Campbell and now Peter Heather. Indeed, the latter's identification (without qualification) of Attila's 'islands of the Ocean' as being those of 'the Atlantic, or west', rather than the Baltic, in his 2005

Fall of the Roman Empire is of particular interest here—given that Heather edited and wrote the new afterword to the 1996 reissue of Thompson's book cited above, his subsequent comments must be read as a clear rejection of Thompson's opinion as to the identity of Attila's islands.(

15)

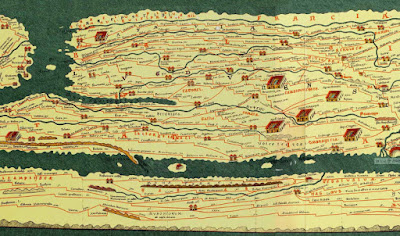

Certainly, an identification of Attila's oceanic possessions with Britain and its associated islands would seem to be a more than credible interpretation of the above passage. First, Orosius, St Augustine, and other writers of Late Antiquity are clear that the British Isles were considered among the 'islands of the Ocean', and Britain was moreover by far the best known and most significant of these islands to the Roman world, having been a Roman province for several hundred years through until the early fifth century. Indeed, the probably fourth-century

Tabula Peutingeriana, an important Late Roman itinerary map, shows little interest in or knowledge of lands lying beyond the northern Roman borders in Europe—whilst the Ocean is depicted as encircling the known world, there are no islands shown to the north of Europe at all, only to the west, where the British Isles and probably originally Thule were depicted.(

16) In light of all of this, it might well be expected that the Western Roman ambassador, Romulus, would have offered a clarification of his reference to 'islands of the Ocean' if Britain and its associated islands were

not meant, and the fact that he does not is something that is at the very least worth noting. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it is clear that Romulus was making a forceful point in his remarks to the Eastern Roman delegation about how exceptional Attila's achievements had been—no previous ruler of Scythia (Central Eurasia) had ever achieved so much as Attila, who had managed to both establish dominion over 'the islands of the Ocean' and

force the Romans to pay him tribute! Needless to say, the thrust of his argument at this point does rather depend on Attila's dominion over these islands being a remarkable, surprising and perhaps even shocking thing to a Roman diplomatic audience; something that was equivalent in its exceptionalness to his forcing the Romans to pay him tribute. In this context, it seems far more plausible that the 'islands of the Ocean' were indeed meant as the well-known and important British Isles, rather than some barely-known (to a Roman audience) islands in the far north.

In sum, given the cultural background of the time and the textual context of the passage in question, the most credible solution is arguably that the Western Roman ambassador to the Huns did indeed believe that Attila ruled in parts of Britain and its associated islands in the late 440s, as Peter Heather, C. E. Stevens and others have indicated in the past. Needless to say, if so, we would thus have two very interesting references to a Hunnic influence on and/or presence in fifth-century eastern Britain: one a contemporary, respected and well-placed Roman ambassador who thought that Attila ruled there (at least for a brief period), and the other a notoriously careful Anglo-Saxon historian who appears to have believed—possibly on the basis of an early tradition or even a written source—that the Anglo-Saxons of the eighth century counted Huns amongst their ancestors. Taken together, these two sources offer a rather intriguing and different perspective on the history of eastern Britain in the mid-fifth century, potentially involving a Hunnic presence in Britain and at least a nominal overlordship of some sort by Attila over parts of this region by the late 440s.

![]() |

| Extract from the probably fourth-century Tabula Peutingeriana, showing Britain at the top left of the map in the Ocean and Gaul across from it, via the nineteenth-century facsimile edition of Konrad Miller; full version available on Wikimedia (image: Wikimedia Commons) |

With regard to the general plausibility and context of such suggestions of Hunnic influence on fifth-century Britain, three final points can be made. First, it needs to be emphasised that modern perspectives on the

Adventus Saxonum now generally reject the traditional date of 449 for the start of continental immigrant activity in eastern and southern Britain, a point of some significance given that any nominal overlordship exercised by Attila is perhaps most easily envisaged as having been over these immigrants. It is clear from the archaeological evidence that 'Anglo-Saxon' groups were established in parts of eastern Britain within the first half of the fifth century, probably by the 430s, and it is furthermore often thought that at least parts of southern Britain were under the direct control of 'Saxon' immigrants from

c. 441 on the basis of the

Gallic Chronicle of 452.(

17) As such, any concerns over a possible conflict between the date by which Attila is said to have possessed rule over the 'islands of the Ocean' in Priscus—by

c. 448—and the date of the

Adventus Saxonum can be easily disposed of.

Second, Lotte Hedeager has recently argued at length that a variety of archaeological and literary evidence indicates that the main 'Anglo-Saxon' homelands of northern Germany and southern Scandinavia were actually conquered and made a part of the Hunnic Empire during the first half of the fifth century, with a Hunnic presence maintained in this region for a period.(

18) Needless to say this is a conclusion of considerable interest to both the present post and the study of the

Adventus Saxonum in general. Certainly, if Hedeager is right, then the idea that the continental immigrants to eastern and southern Britain included Huns amongst their number and that there was a degree of Hunnic overlordship for at least the areas of Britain that had fallen under the immigrants' sway by the 440s would seem rather less surprising than might otherwise perhaps be the case.

Third and finally, it should be noted that there is a small amount of additional archaeological, literary and linguistic evidence that may, just possibly, offer support for any theory of a Hunnic presence and overlordship in fifth-century Britain. On the archaeological front, for example, it can be observed that the small number of gold open-ended earrings that Hedeager identifies as Hunnic in origin and indicative of the presence of Huns in Denmark are not confined to this part of north-western Europe alone. At least one gold earring of a very similar design and size is known from Britain too, and if Hedeager's identification of such items as Hunnic is upheld for the Danish examples, then there seems no obvious

a priori reason why it should not be applied to any British examples too.(

19) Likewise, a Dyerkan-type cicada brooch that was found in Suffolk and now housed in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, may be of some potential interest in the present context, given that this type of dress-accessory is believed to have its origins in the early to mid-fifth century and is found primarily in the Middle Danube, the Black Sea area and the Northern Caucasus.(

20)

On the literary and linguistic front, Hedeager has argued for southern Scandinavia that the royal sagas of the Skjoldunge–Skilfinger tradition preserve the memory of a period of Hunnic rule in that region, with the early Norse rulers

Haldan,

Roo,

Ottar and

Adils corresponding in name and details to the fifth-century Hunnic kings

Huldin,

Roas,

Octar and

Attila.(

21) Whilst England lacks such a neat set of apparent correspondences, there are nonetheless a few hints which might point in a similar or related direction. Perhaps the most interesting of these occurs in the

genealogy of the kings of Kent—the

Oiscingas—preserved by Bede in his

Historia Ecclesiastica II.5, where we find the name

Octa recorded as that of the son of the probably divine dynastic progenitor

Oisc, with

Octa being both a name that seems not to have been otherwise used in Anglo-Saxon England and one that is very close in form to the Hunnic name

Octar (Attila's uncle and one of his predecessors as ruler of the Hunnic Empire). Needless to say, in light of Hedeager's discussion of the Norse names, this is most intriguing, and it is worth noting here that Old English

Octa is indeed generally linked by researchers with the Norse name

Ottar mentioned above. Quite what this all means is open to debate, but one wonders whether it might not reflect at least some sort of early claim to either Hunnic descent or links on the part of the

Oiscingas dynasty, to put alongside their potential claim to Gothic ancestry that was noted above?(

22)

This is probably as far as we can sensibly go at present. On the whole, it would seem that there is at least a case to be made for a degree of Hunnic involvement in fifth-century Britain. Not only does the simplest and most common interpretation of Bede's

Historia Ecclesiastica V.9 imply that the latter believed that the Anglo-Saxons partly derived their origins from Huns, but a mid-fifth-century Roman ambassador also arguably thought that Attila ruled over the British Isles in the late 440s. Taken together, these two sources are certainly suggestive, and a small number of finds and names from pre-Viking England may offer some additional support here too. Furthermore, such a scenario may actually have a reasonable potential context. On the one hand, it is now generally agreed that the situation in the fifth and earlier sixth centuries in eastern Britain was rather more ethnically complex than has been sometimes assumed, with the post-Roman immigrants to Britain including individuals and groups drawn from a number of continental tribes and confederations, including potentially Danes, Swabians and Goths. On the other hand, Lotte Hedeager has recently argued that the main Anglo-Saxon homelands in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia were, in fact, under Hunnic rule in the first half of the fifth century and saw a Hunnic presence then, something that, if true, would clearly offer a credible context for any contention that there were Huns amongst the mid-fifth-century 'Anglo-Saxon' immigrants to Britain and that those parts of the island under 'Saxon' control after

c. 441 were at least nominally also under Hunnic overlordship by the late 440s. As such, whilst the case cannot be said to be proven and is perhaps surprising, it does deserve at least some serious consideration.

Notes1 Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica, I.15, trans. B. Colgrave, in J. McClure & R. Collins (edd.), Bede: the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Oxford, 1994), p. 27. Bede similarly describes the immigrants as 'The people of the Angles or of the Saxons' in his Greater Chronicle of 725 (sa. 4410: McClure & Collins, Bede, p. 326).2 For example, J. Hines, 'The origins of East Anglia in a North Sea Zone', in D. Bates & R. Liddiard (edd.), East Anglia and its North Sea World in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge, 2013), pp. 16–43, esp. pp. 38–9; B. A. E. Yorke, 'Anglo-Saxon gentes and regna', in H-W. Goetz, J. Jarnut & W. Pohl (edd.), Regna and Gentes: The Relationship Between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World (Leiden, 2003), pp. 381–408, esp. pp. 385–90; C. Scull, 'Approaches to the material culture and social dynamics of the migration period in eastern England', in J. Bintliff and H. Hamerow (edd.), Europe Between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Oxford, 1995), pp. 71–83; H. Hamerow, 'The earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms', in P. Fouracre (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, I: c.500–c.700 (Cambridge, 2005), pp. 263–88, esp. pp. 268–70; H. Härke, 'Anglo-Saxon immigration and ethnogenesis', Medieval Archaeology, 55 (2011), 1–28 at p. 11; T. Williamson, 'The environmental contexts of Anglo-Saxon settlement', in N. J. Higham & M. J. Ryan (edd.), The Landscape Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England (Manchester, 2010), pp. 133–56 at pp. 147–52; S. Lucy, The Anglo-Saxon Way of Death (Stroud, 2000), p. 4; and also T. Martin, Identity and the Cruciform Brooch in Early Anglo-Saxon England: An Investigation of Style, Mortuary Context, and Use, 4 vols. (University of Sheffield PhD Thesis, 2011), I.152–91. Note, with regard to Angles and Saxons, it should be remembered that contemporary sources do indeed mention both groups as present in fifth- to sixth-century Britain—Angles are mentioned as a major immigrant group in Britain by Procopius in the 550s (

History of the Wars, VIII.xx), whilst Saxons are mentioned in the

Gallic Chronicle of 452 and by Gildas in his

De Excidio Britanniae of

c. 540 or before.

3 See J. Hines, The Scandinavian Character of Anglian England in the Pre-Viking Period, BAR British Series 124 (Oxford, 1984), and J. Hines, 'The Scandinavian character of Anglian England: an update', in M. O. H. Carver (ed.), The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-western Europe (Woodbridge, 1992), pp. 315–29; see also now Hines, 'The origins of East Anglia', from which the quotation given above is taken (p. 39). Note, with regard to the 'Anglian' material that forms the 'core' of the immigrant culture in this region, as per Hines, see Green, Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire AD 400–650 (Lincoln, 2012), fig. 21a & pp. 93–5, and Williamson, 'Environmental contexts of Anglo-Saxon settlement', pp. 147–52, for two arguably complementary explanations for its distribution in early Anglo-Saxon England.4 V. I. Evison, The Fifth-Century Invasions South of the Thames (London, 1965); J. Soulet, 'Between Frankish and Merovingian influences in Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex (fifth–seventh centuries)', in S. Brookes et al (edd.), Studies in Early Anglo-Saxon Art and Archaeology: Papers in Honour of Martin G. Welch (Oxford, 2011), pp. 62–71; and S. Harrington & M. Welch, The Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms of Southern Britain AD 450–650: Beneath the Tribal Hidage (Oxford, 2014), especially pp. 174–210. On Thuringians, see I. N. Wood, 'Before and after the migration to Britain', in J. Hines (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons From the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: an Ethnographic Perspective (Woodbridge, 1997), pp. 41–64 at pp. 42, 44, 45. On Visigoths, see the cautious remarks in J. Schuster, P. Andrews & R. Seager-Smith, 'A late 5th–early 6th century context from Springhead, Kent', Lucerna, 31 (2006), 2–3.5 S. Newton, 'Beowulf and the East Anglian royal pedigree', in M. O. H. Carver (ed.), The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-western Europe (Woodbridge, 1992), pp. 65–74; S. Newton, The Origins of Beowulf and the Pre-Viking Kingdom of East Anglia (Woodbridge, 1993); B. Yorke, 'Political and ethnic identity: a case study of Anglo-Saxon practice', in W. O. Frazer & A. Tyrell (edd.), Social Organisation in Early Medieval Britain (London, 2000), pp. 69–89 at pp. 80–1. On an Anglo-Saxon knowledge of and interest in the Goths pre-dating the ninth-century, see for example L. Neidorf, 'The dating of Widsið and the study of Germanic antiquity', Neophilologus, 97 (2013), 165–83, esp. pp. 172–3. On the name Oisc < *Anskiz/*Anschis, see P. Sims-Williams, 'The settlement of England in Bede and the Chronicle', Anglo-Saxon England, 12 (1983), 1–41 at pp. 22–3 and fn. 94. With regard to a Gothic element in Kent, see also perhaps the Visigothic brooch from Springhead, Kent, discussed in Schuster et al, 'A late 5th–early 6th century context from Springhead, Kent', 2–3.

6 Procopius, History of the Wars, VIII.xx: 'Angíloi, Frísonnes kaì Brítannes', see E. A. Thompson, 'Procopius on Brittia and Britannia', Classical Quarterly, 30 (1980), 498–507.7 See E. Ekwall, 'Tribal Names in English Place-Names', Namn Och Bygd, 41 (1953), 129–77 at p. 150; V. E. Watts, The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names (Cambridge, 2004), pp. 213 [Elm], 592 [Swaffhams], 602 [Tealby]; Green, 'Tealby, the Taifali, and the End of Roman Lincolnshire', Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 46 (2011), 5–10; F. W. Moorman, 'English Place-Names and Teutonic Sagas', Essays and Studies, 5 (1914), 75–103 at pp. 95–9 [Burgundian Volsungs may lie behind the early Norfolk place-name Walsingham]; M. Gelling & A. Cole, The Landscape of Place-Names (Stamford, 2000), p. 70 [Denver, Norfolk, a 'very early' place-name meaning 'the Danes' crossing', reflecting the presence of Danes 'much earlier than the Viking period']; H. F. Nielsen, The Germanic Languages: Origins and Early Dialectal Interrelations (Tuscaloosa, 1989), p. 62 [Tyringham, Buckinghamshire, and related names may reflect settlements of Thuringians]. On the name Suebdæg, see Neidorf, 'The dating of Widsið', p. 176, and H. Ström, Old English Personal Names in Bede's History: An Etymological-phonological Investigation (Lund, 1939), p. 35; a name in the East Saxon royal genealogy, Swæppa, may similarly derive from the Old English form of the ethnonym Swabian, see Ström, Old English Personal Names in Bede's History, p. 35, and M. Redin, Studies on Uncompounded Personal Names in Old English (Uppsala, 1919), pp. 69, 109.8 Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica, V.9, trans. Colgrave, in McClure & Collins (edd.), Ecclesiastical History, p. 247.9 For example, D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English (Oxford, 2012), p. 29, and especially R. H. Bremmer Jr, 'The nature of the evidence for a Frisian participation in the Adventus Saxonum', in A. Bammesberger & A. Wollmann (eds.), Britain 400–600: Language and History (Heidelberg, 1990), pp. 353–71 at pp. 356–9.10 J. Campbell, 'The first century of Christianity in England', in J. Campbell, Essays in Anglo-Saxon History (London, 1986), pp. 49-67 at p. 53 and fn. 25 [first quotation]; J. Campbell, 'The lost centuries: 400–600', in J. Campbell (ed.), The Anglo-Saxons (London, 1982), p. 31 [second quotation]. See also J. Campbell, 'The Age of Arthur [review article]', Studia Hibernica, 15 (1975), 177–85 at p. 179.11 See, for example, Yorke, 'Anglo-Saxon gentes and regna', p. 387; J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People: A Historical Commentary (Oxford, 1988), p. 181; D. P. Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, revised edition (London, 2000), p. 13; and Campbell, 'The lost centuries: 400–600', p. 31. See also Wood, 'Before and after the migration to Britain', pp. 41–5.12 Campbell, 'Age of Arthur', quotation at p. 179; Campbell, 'The lost centuries: 400–600', p. 31. On the Rugii and Bructeri taking part in Attila's invasion of Gaul in 451, see for example Sidonius Apollinaris's contemporary Carmina, VII.321–5.13 Wood, 'Before and after the migration to Britain', p. 41.14 Priscus, Fragments 11.2: R.C. Blockley The Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire: Eunapius, Olympiodorus, Priscus and Malchus 2 vols. (Liverpool, 1983), vol. II, p. 277.15 E. A. Thompson, A History of Attila and the Huns (Oxford, 1948), quotation at p. 75, repeated by Lotte Hedeager in her recent Iron Age Myth and Materiality: An Archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400–1000 (London, 2011), p. 193, with a reference to the 1996 largely-unchanged reissue of Thompson's 1948 book; note, the 1996 reissue was edited by Peter Heather and contained an afterword by him, with a new shortened title of The Huns (Oxford, 1996). The other works referenced here are: T. Mommsen, Gesammelte Schriften (Berlin, 1906), vol. IV, p. 539 fn. 5; J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire, 2 vols. (London, 1923), vol. I, p. 277 fn. 4; C. E. Stevens, 'Gildas Sapiens', English Historical Review, 56 (1941), 353–73 at p. 363 fn. 7; Campbell, 'Age of Arthur', p. 179; J. Campbell, 'Observations on the Conversion of England', in J. Campbell, Essays in Anglo-Saxon History (London, 1986), pp. 69–84 at p. 70 fn. 5; P. Heather, The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History (London, 2005), p. 334.16 S. F. Johnson, 'Travel, Cartography, and Cosmology', in S. F. Johnson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity (Oxford, 2012), pp. 562–94; R. Talbert, Rome's World: The Peutinger Map Reconsidered (Cambridge, 2010). A. D. Lee, Information and Frontiers: Roman Foreign Relations in Late Antiquity (Cambridge, 1993), pp. 89–90, comments usefully on the Romans lacking a conceptual framework for Europe north of the Danube and the Rhine, noting that the Tabula Peutingeriana offers barely any topographical information for these regions.17 See, for example, N. J. Higham & M. J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven & London, 2013), pp. 59, 76, 104, 114–15.18 L. Hedeager, Iron Age Myth and Materiality: An Archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400–1000 (London, 2011), especially pp. 191–228, and L. Hedeager, 'Scandinavia and the Huns: an interdisciplinary approach to the Migration Era', Norwegian Archaeological Review, 40 (2007), 42–58; see also perhaps M. Görman, 'Influences from the Huns on Scandinavian Sacrificial Customs during 300-500 AD', in T. Ahlbäck (ed.), The Problem of Ritual (Åbo, 1993), pp. 275–98, especially pp. 295–6. It should be noted that one piece of her evidence for this interpretation is explicitly rejected in the above discussion (Thompson's 1948 claim that 'he islands of the Ocean' are universally agreed to be the Baltic islands, see above and fn. 15), but she marshals much other evidence too in support of a period of Hunnic dominion over southern Scandinavia which isn't contradicted by the analysis offered here.19 Hedeager, Iron Age Myth and Materiality, pp. 198, 200, fig. 9.2; Hedeager, 'Scandinavia and the Huns', pp. 7, 9, fig. 5. See also the debate in U. Näsman, 'Scandinavia and the Huns: a source-critical approach to an old question', Fornvännen, 103 (2008), 111–18, and especially L. Hedeager, 'Paradigm exposed: reply to Ulf Näsman', Fornvännen, 103 (2008), 279–83. Compare the earrings illustrated by Hedeager in Iron Age Myth and Materiality, fig. 9.2, and 'Scandinavia and the Huns', fig. 5, with, for example, Portable Antiquities Scheme NCL-ADA2E4, found in Yorkshire.20 I. Gavritukhin & M. Kazanski, 'Bosporus, the Tetraxite Goths and the Northern Caucasus region during the second half of the fifth and the sixth centuries', in F. Curta (ed.), Neglected Barbarians, Studies in the Early Middle Ages vol. 32 (Turnhout, 2010), pp. 83–136 at pp. 132–3 and fig. 4.29; A. MacGregor, A Summary Catalogue of the Continental Archaeological Collections in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, 1997), pp. 267–8.21 Hedeager, Iron Age Myth and Materiality, pp. 189–90, 224–8.22 On Octa and Ottar, see Ström, Old English Personal Names in Bede's History, p. 72; Redin, Studies on Uncompounded Personal Names in Old English, p. 77. On the Gothic links of the Oiscingas of Kent, see further above and fn. 5, along with Yorke, 'Political and ethnic identity: a case study of Anglo-Saxon practice', pp. 80–1; it is perhaps interesting to note that both Octa's father and his son in Bede's genealogy bear names with Gothic links, given the close association between the Goths and the Huns in the early to mid-fifth century. Other intriguing linguistic and literary hints from England include the possibility that a number of Anglo-Saxon personal names derive from the Old English ethnonym Hunas/Hune, 'the Huns', something which would be very suggestive if true: Ström, Old English Personal Names in Bede's History, p. 25; D. Rollason & L. Rollason (eds.), The Durham Liber Vitae. II: Linguistic Commentary (London, 2007), p. 130; and cf. above and fn. 7 on Old English personal names such as Suebdæg. Also of potential interest are the medieval East Anglian tales that appear to treat Attila the Hun as an early medieval ruler of Norfolk with a base at Attleborough, a place-name that is Old English for 'fortified place belonging to Ætla (< Attila)', particularly as one of these is thought to preserve an otherwise lost 'heroic' tale of a fight between Attila and Hunuil/Unwen: see further C. E. Wright, The Cultivation of Saga in Anglo-Saxon England (Edinburgh and London, 1939), pp. 121–2; A. Bell, ‘Gaimar’s early “Danish” kings’, Proceedings of the Modern Language Association, 65 (1950), 601–40 at pp. 608–10; C. Brett, 'Hunuil-Unwine-Unwen', Modern Language Review, 15 (1920), 77; R. W. Chambers, Widsith: A Study in Old English Heroic Legend (Cambridge, 1912), p. 219 on Hunuil/Unwen; and Watts, Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names, p. 26 on Attleborough.The content of this post and page, including any original illustrations, is Copyright © Caitlin R. Green, 2015, All Rights Reserved, and should not be used without permission.